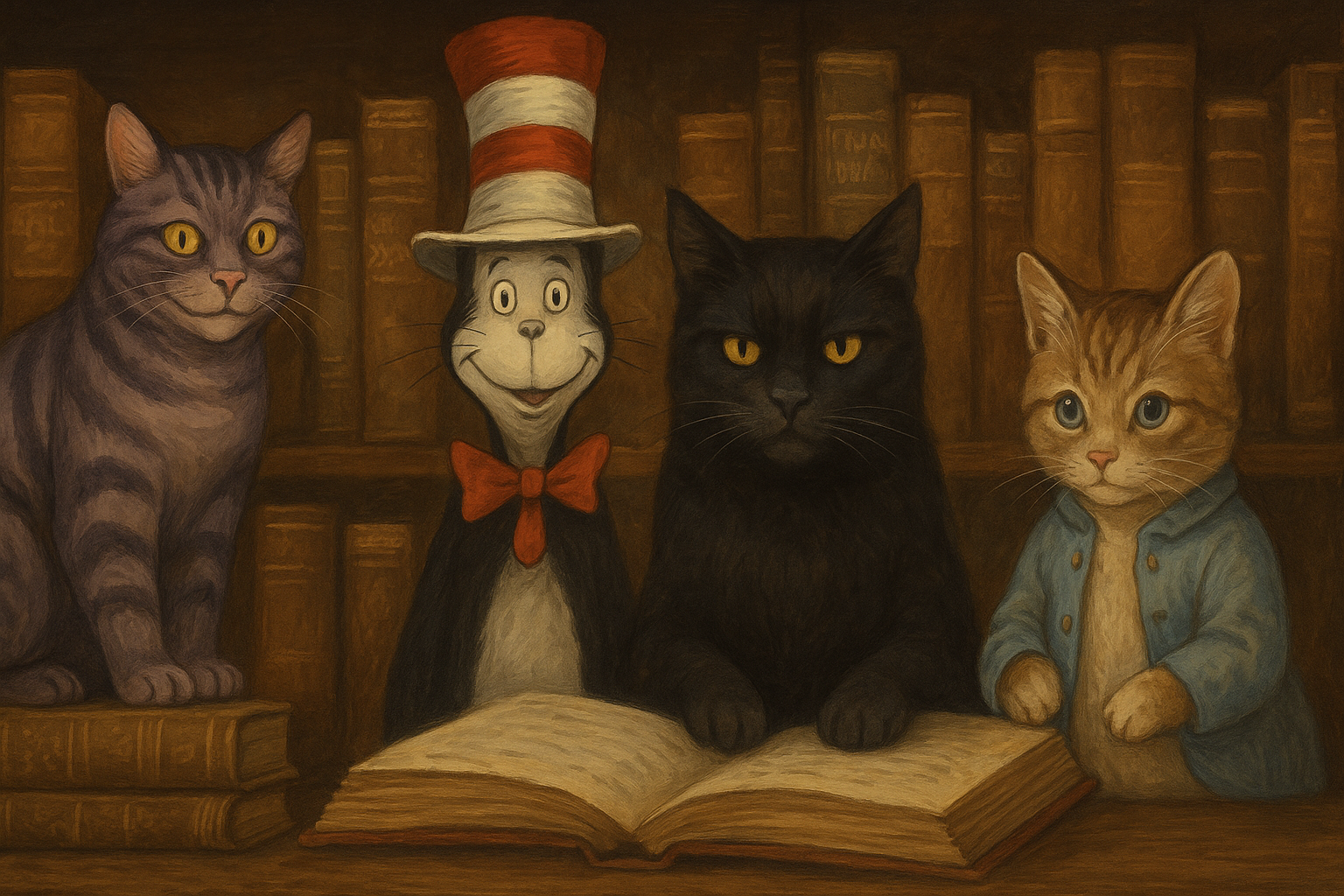

If you’ve ever curled up with a good book and a purring cat, you’re not alone. Cats have prowled through the pages of literature for centuries—sometimes sly and sinister, other times adorable or aloof. From classic novels and poetry to magical children’s tales and crime-solving cozies, our feline friends have inspired some of the most iconic stories ever written.

In this guide, we’ll explore some of the most memorable literary cats, the authors who adored them, and why these mysterious creatures make the perfect muses. Whether you’re a bookworm, a cat lover, or both, you’ll find plenty to purr about.

Famous Cats in Classic Literature

One of the most enduring feline figures in literature is the Cheshire Cat from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). With that eerie grin and knack for disappearing mid-sentence, the Cheshire Cat perfectly captures the cat’s enigmatic nature. (Fun fact: the phrase “grinning like a Cheshire cat” predates Carroll’s novel by over 50 years!)

Other authors drew on their own cats for inspiration. Beatrix Potter, known for The Tale of Tom Kitten (1907) and The Tale of Samuel Whiskers (1908), modeled her characters after the cats who lived on her English farm. These kitties aren’t just adorable—they’re also mischievous troublemakers who ruin outfits and narrowly escape becoming rat dinner!

In Rudyard Kipling’s The Cat That Walked by Himself (1902), the feline is clever, proud, and fiercely independent—traits any modern cat owner will recognize. This short story shows a cat who earns a warm spot by the fire but never loses his wild streak.

Even Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat (1957) brought chaos in a tall striped hat, proving cats could headline children’s books and become household names for generations.

Cats in Mystery and Magic

In adult fiction, cats don’t always play nice. Meet Behemoth, the gun-toting, sardonic, bipedal black cat from The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. A servant of the devil, Behemoth steals scenes with his chaotic energy and biting wit.

Then there’s the chilling tale of revenge in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Black Cat (1843), where a murdered feline returns to haunt its abusive owner. Not your average bedtime story—but unforgettable nonetheless.

Fast forward to modern times, and the “cat cozy mystery” subgenre has exploded. Sleuthing cats like Joe Grey in Shirley Rousseau Murphy’s series or Koko and Yum Yum in Lillian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who… novels have helped solve everything from theft to murder—often outwitting the humans around them.

Cats in Poetry: From Keats to Eliot

Poets have long found inspiration in cats’ quiet elegance and quirky charm. In 1748, Thomas Gray wrote “Ode on the Death of a Favorite Cat Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes,” a playful yet tragic tribute. John Keats praised a wheezy feline in “Sonnet to a Cat,” while William Wordsworth captured a kitten’s delight in fallen leaves.

But it’s T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939) that remains the most beloved collection of cat poetry. These character sketches—like the mischievous Macavity or the theatrical Gus—later inspired Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats the musical. Eliot’s love for feline antics and mystery practically leaps off the page.

Real-Life Writers and Their Cats

Authors aren’t just writing about cats—they’re living with them, too. Dr. Samuel Johnson adored his cat Hodge so much that there’s a statue of Hodge outside Johnson’s London home, proudly sitting atop a dictionary.

Charles Dickens may have written sinister cat scenes in his novels, but he deeply loved his pets—and allegedly kept the paw of a favorite cat as a keepsake.

And then there’s Ernest Hemingway, whose polydactyl cats (with extra toes!) have become legends in their own right. Today, over 40 descendants of his original cat, Snowball, roam the Hemingway House in Key West, Florida—each one as confident and laid-back as the author himself.

Cat Books Worth Reading (For All Ages)

- The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide – A quiet, poetic novella about a stray cat who changes a couple’s life.

- The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa – A heartwarming road trip story told through the eyes of a cat.

- Dewey: The Small-Town Library Cat Who Touched the World by Vicki Myron – A true story of a kitten who stole a town’s heart.

- The Cat Who Could Read Backwards by Lilian Jackson Braun – A purrfect intro to feline mysteries.

- Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats by T.S. Eliot – Classic poems that continue to inspire cat lovers and musicals alike.

Final Thoughts

From mischievous misfits to magical muses, cats have claimed their rightful place in literature—as mysterious, charming, and sometimes chaotic companions to both readers and writers. Their presence in poetry, fiction, and real-life author stories reminds us that cats are more than pets—they’re storytellers in fur.

So next time your cat curls up on your keyboard or sits on the book you’re trying to read… maybe they’re just trying to add a chapter of their own.

Cats in Literature FAQs

What is the most famous cat in literature?

The Cheshire Cat from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is often considered the most iconic literary cat, known for its mysterious grin and vanishing act.

What books feature cats as main characters?

Popular examples include The Guest Cat by Takashi Hiraide, The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa, and Carbonel by Barbara Sleigh.

What inspired T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats?

T.S. Eliot originally wrote whimsical poems about cat personalities for children in his life; these poems were later collected into Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, which inspired the musical Cats.

Did Ernest Hemingway really have cats?

Yes. Ernest Hemingway famously kept polydactyl (extra-toed) cats at his Key West home. Today, more than 40 of their descendants still live at the Hemingway House.

What genre are cat mystery novels?

Cat mysteries are a cozy mystery subgenre where cats often help solve crimes. A classic entry point is Lilian Jackson Braun’s The Cat Who… series.