Heart disease, with subsequent heart failure, is one of the most frequent problems in small-animal medicine. Because the heart functions to supply oxygen and nutrients to the rest of the body via the blood, serious ramifications result if this function is interfered with by disease.

Table of Contents

In addition, the decreased movement of blood through the circulatory system caused by a faulty heart leads to high blood pressure, and fluid buildup within the abdomen and/or the lungs (congestive heart failure), depending on which side of the heart is involved.

If the latter structures do become waterlogged, oxygen exchange is reduced even further.

Mitral Insufficiency and Other Valve-Related Disorders

Different diseases involving the heart valves or heart muscle can lead to heart failure. By far the most common type of heart disease seen in cats, aside from that caused by heartworms, is mitral insufficiency, which involves the heart valve separating the left atrium from the left ventricle.

If this valve becomes diseased and fails to close properly when it is supposed to, blood is allowed to flow back into the left atrium when the left ventricle contracts.

This has two effects: (1) The amount of blood pushed forward into circulation by each heart contraction is greatly reduced, which means that the heart (which, remember, is diseased) must work harder than it did when it was healthy to keep up with the body’s demand for blood; and (2) the backup of blood that occurs as a result of the inefficient heart contraction leads to fluid buildup within the lungs, interfering with oxygen exchange between the blood and the lungs.

As a result, a vicious cycle develops. Mitral insufficiency can result from normal wear and tear associated with age, or—more importantly—it can appear secondary to other diseases, namely, periodontal disease.

Bacteria from the diseased teeth and gums can enter the bloodstream and attach to the heart valve, setting up infection and inflammation. Over time, the heart valve becomes damaged and scarred, making it unable to function properly.

The end result is often heart failure. Although their frequency is much less, diseases involving the other valves in the heart can nevertheless occur. Disease of the tricuspid valve, which separates the right chambers of the heart, can occur secondary to age or infection and can interfere with the normal return of blood to the heart from the body.

Defects in the pulmonic or aortic valves, which separate the ventricles from the pulmonary vessels and aorta, respectively, are usually congenital (present at birth) and might not be detectable when the kitten is young.

However, as the cat matures and the requirements placed on the heart increase, signs of heart disease or failure could become apparent.

Cardiomyopathy

Changes in the thickness and/or contractility of the muscles making up the heart are termed cardiomyopathies. The two main types of cardiomyopathies that dogs and cats can suffer from are hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy.

In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the muscular heart walls become excessively thickened, shrinking the chambers of the heart and disrupting normal filling of the heart with blood. With dilated cardiomyopathy, the opposite occurs:

The heart walls become thin and weak, making normal contractions difficult. Regardless of the type, a cardiomyopathy can lead to overt heart failure if progression occurs. Cardiomyopathies are more prevalent in cats than they are in dogs.

Middle-aged male cats seem to be affected the most. In addition, Siamese, Burmese, and Abyssinian cats appear to have a higher incidence of this disorder than do other breeds. The causes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in cats remain unknown; however, researchers have found a link between dilated cardiomyopathy and dietary deficiencies in the amino acid taurine.

An increased lethargy and loss of appetite might be the initial signs seen in cats with cardiomyopathies. Other more advanced clinical signs can include coughing, difficulty in breathing, and overt collapse.

Vomiting can also become a factor, especially if there is secondary kidney damage caused by poor blood circulation. In addition, hind-end weakness and muscular pain due to aortic thromboembolism can be seen in these cats.

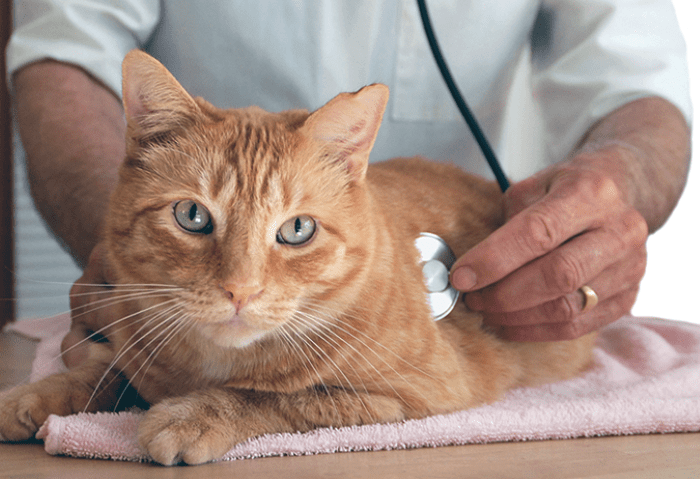

These clinical signs can help lead a veterinarian to a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy in a cat. Using a stethoscope, the veterinarian can detect rapid heart rates, abnormal rhythms, and heart murmurs as well.

Radiographic X rays and ultrasound show abnormal heart shapes, abnormal heart wall thickness, and, if heart failure is present, fluid buildup within the thorax in these cats. Electrocardiograms are useful in determining the extent of any heart enlargement and to assess the electrical conduction occurring within the heart walls.

If a taurine deficiency is suspected, measuring blood levels of this amino acid can prove or disprove such suspicions. Treatment of cardiomyopathy consists of medications designed to reduce blood pressure and to increase the efficiency of heart contractions.

Drugs designed to move fluids out of the lungs might also be prescribed. In cats with advanced heart failure, oxygen therapy might be necessary. Obviously, for those cats with taurine-deficiency cardiomyopathy, taurine supplementation should also be used to normalize cardiac function.

Unfortunately, little can be done to reverse the anatomic changes to the heart seen in most cardiomyopathies. With supportive treatment, however, the quality of life of affected felines can be maintained at a good level for months, even years.

Birth Defects

Birth defects involving the heart wall (septal defects), the heart valves (valvular stenosis), or the vessels leaving the heart (patent ductus arteriosus) can increase the workload placed on the heart and can lead to heart failure as the affected pet gets older.

If detected early enough, many of these defects can be surgically corrected at a young age, before associated signs become severe. In those that cannot be repaired, treatment is similar to that of other forms of heart disease.

Symptoms of a Failing Heart

Regardless of the inciting cause, the clinical signs associated with a failing heart include coughing (especially at night and after exercise), breathing difficulties, distended abdomen, weight loss, and exercise intolerance.

Suffering pets might stand with their front legs spread wide apart and their necks lowered and extended to afford the passage of more air into the lungs. Affected dogs and cats might collapse even after the slightest exertion or excitement.

If the right side of the heart is involved, owners might notice a bulging abdomen. This occurs secondarily to a backup of blood within the abdominal vessels, leading to a fluid buildup within the abdominal cavity.

All of these signs might start off subtly, yet they usually progressively worsen as the disease progresses and failure begins.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of heart disease or heart failure is made using clinical signs, radiographs, ultrasound, and/or electrocardiogram findings. In addition to the classic clinical signs listed above, many forms of heart disease are accompanied by heart murmurs, which can be detected by a veterinarian on listening to the chest using a stethoscope.

A heart murmur is an irregular sound caused by the disruption of normal blood flow within the heart. By far the majority of heart murmurs heard are caused by diseases of the heart valves and the abnormal blood flow through these valves that results.

Still other murmurs can originate from the defects in the heart muscle or vessels that alter normal blood flow. Unusually forceful and rapid heart contractions, such as those seen within overly excited animals or in pets suffering from anemia, can even lead to an irregular heart sound.

Interestingly, murmurs are not commonly detected in dogs suffering from heartworm disease, even when their hearts are full of the parasites. Heart murmurs are usually classified according to their intensity as heard through a stethoscope.

A trained veterinarian can identify which portion of the heart is affected and arrive at a diagnosis just by pinpointing the area on the chest where the murmur is the loudest, and by determining when the murmur occurs, whether it is during the heart’s contraction phase, relaxation phase, or both.

Other Diagnostic Tests

One parameter that cannot be determined from the intensity of a heart murmur is the stage of heart disease or failure the animal is in. For instance, severe mitral insufficiency might not be associated with any murmur whatsoever, whereas a loud one might accompany an early case.

This is because in the later stages, the valve might become so diseased and worn that it offers so little resistance to blood flow back through it that a murmur-causing disruption of blood flow might not arise.

Radiographs and/or ultrasonography of the chest are essential for establishing a diagnosis of heart disease. Animals with primary lung disease, including pneumonia, can exhibit clinical signs very similar to those seen in patients with heart failure, and these tests are needed to differentiate the two.

Diseased hearts will appear abnormally enlarged on both tests. This enlargement can occur in compensation for the heart having to work harder to pump blood, or it could be due to a thinning and bulging of the heart wall resulting from constant bombardment with high-pressure streams of blood escaping through faulty heart valves.

Regardless of the cause, an enlarged heart, combined with clinical signs or murmurs, signifies heart disease. If such a combination exists, the next test most practitioners will perform is an electrocardiogram.

The electrocardiogram (ECG; often phonetically pronounced EKG) is a test used widely to assess the condition of the heart. Remember that a heartbeat is produced when a wave of electrical energy moves through the tissues of the chambers, starting in the atria and moving down to the ventricles.

This electrical wave then makes the muscle wall of these chambers contract, pumping out the blood contained within. The ECG helps evaluate the status of this electrical conduction system, and at the same time, can give the veterinarian useful information regarding the size of the heart itself, and indirectly, the condition of the heart as a pump. In addition, with the information gained from an ECG, proper drug treatment dosages can be more easily established.

Treatment

Because most cases of heart disease or failure are nonreversible, the treatment goal for any dog or cat suffering from such a condition is to create an environment that relieves some of the workload on the heart and slows the progression of the disease.

Canines and felines with bad hearts need to be fed special diets that are moderately restricted in sodium to help reduce blood pressure and discourage the accumulation of fluid within the lungs and/or the abdomen. Diets formulated especially for this purpose are available from veterinarians.

Diuretic drugs are also used in heart failure patients to help mobilize and eliminate excessive fluid that might be accumulating within the body. In many instances, this diuretic therapy, combined with a low-sodium diet, might be all that it takes to relieve the coughing and discomfort seen in affected pets.

Remember that a dog or cat on diuretic medication will drink lots of water and urinate with greater frequency, so be sure to provide it with plenty of water to drink at all times, and be prepared for plenty of walks outside or frequent trips to the litterbox.

Medications designed to dilate the blood vessels, making it easier for the diseased heart to pump blood through them, are usually the next in line if the special diet and diuretics don’t seem to be enough to correct the problem.

If none of the treatment regimens described above prove effective, the final medicating step often taken to manage the heart failure is to give drugs designed to help slow and strengthen the heart’s contraction.

Such medications can have many undesirable and serious side effects if a veterinarian does not carefully monitor therapy, but, on average, they will prolong the life of a pet in heart failure for an average of 4 to 6 months.